It’s not every day you get the chance to chat with a double Paralympic medallist, but when he’s part of the JudoScotland office team, that opportunity becomes a little more accessible. We spoke to Sam Ingram about the differences in Paralympic judo, his own success at the Games, and how important it is to support the sport at the grassroots level.

Q: What is the key difference in Paralympic judo compared to Olympic judo?

A: The main difference in Paralympic judo is that the athletes start the match already gripped up. Before the referee says “hajime,” the competitors take a sleeve and lapel grip on each other. If the athletes have opposite stances, such as left versus right, the referee decides who gets the dominant grip. Aside from the starting position, all other aspects of the contest, including techniques, match duration, and the shido system, remain the same.

For spectators, the gripped-up start can make the matches more exciting, as there’s no waiting around—the action begins immediately. However, this can also lead to some athletes becoming too defensive, though typically, it results in fast-paced and intense bouts. Starting from a gripped position places more emphasis on strength and speed from the very beginning.

Q: How are Paralympic judoka categorised?

A: In Paralympic judo, athletes are divided into different categories based on their level of vision. Judoka are classified into either J1 or J2 categories, with J1 being for those who are more severely visually impaired.

Q: How integrated are Paralympic and Olympic judo training environments?

A: One of the great things about judo is that it allows for a high level of integration between athletes aiming for the Olympics and those aiming for the Paralympics. It’s common to see judoka with disabilities training in mainstream clubs because judo is highly adaptable. This integration is a testament to the flexibility and inclusiveness of the sport.

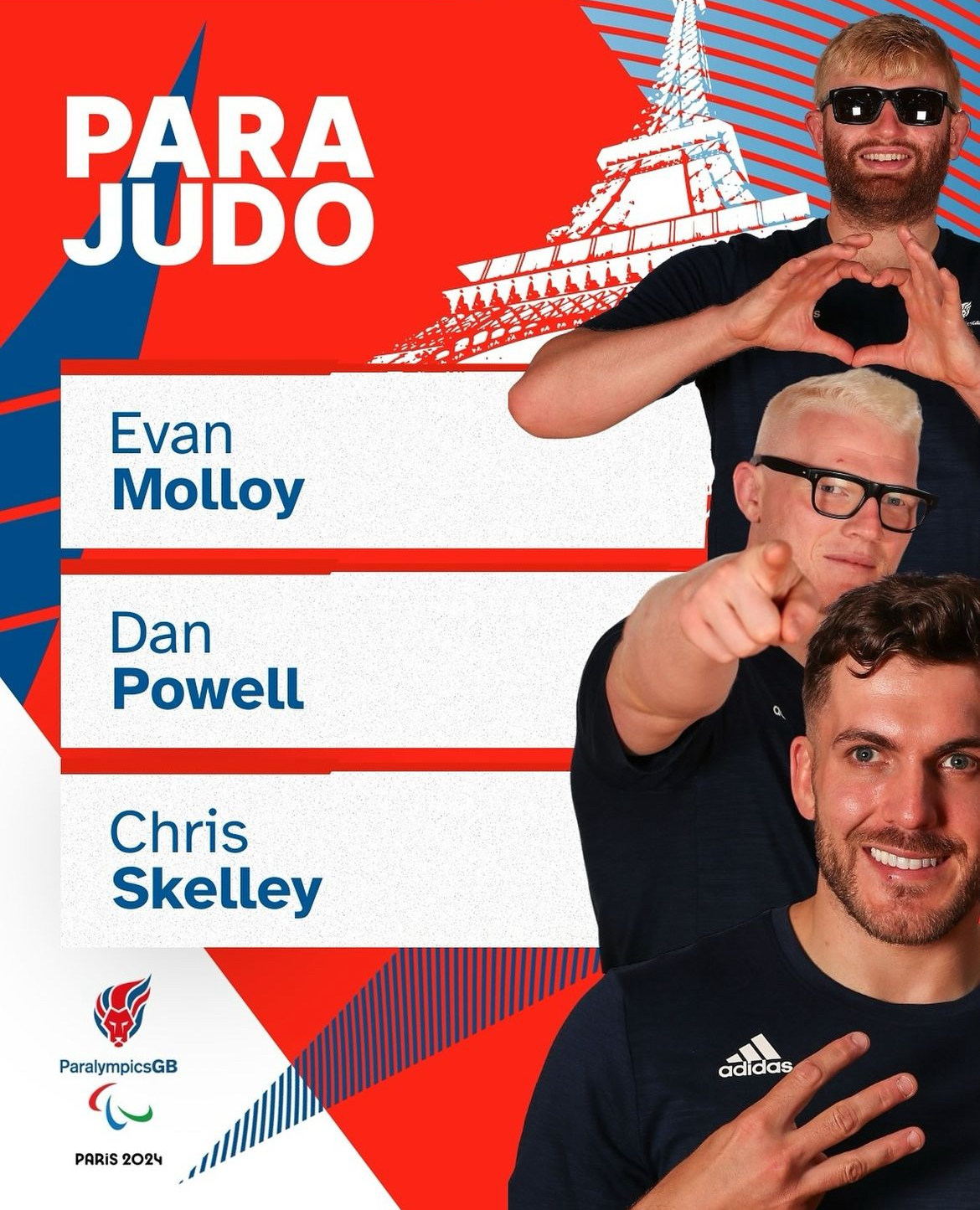

Q: The British team is looking strong this year with Dan Powell, Evan Molloy, and Chris Skelly all aiming to medal. What can you tell us about them?

A: It’s a really solid team this year. Starting with Evan Molloy, he’s the up-and-comer of the group. While he’s a younger athlete in a tough category with many high-level competitors, I think he has the potential to secure a medal. Every success begins with that first big result, and I’m excited to see how he performs.

Dan Powell, on the other hand, is an experienced athlete with a strong chance of medaling. He competed in his first Games in 2012 and comes from a family deeply involved in judo. His background and experience make him a strong medal contender.

Chris Skelly is another standout, already a Paralympic champion with a proven track record of success. Although the recent weight classification change has been a challenge, he’s adapted well, and I’m confident in his chances.

These three have put in an incredible amount of effort and time into their preparation. As a team, Britain has a strong Paralympic judo reputation, with the world holding different expectations compared to our Olympic team. We’re seen as frontrunners and have performed well for a long time. While things don’t always go as planned, other nations are definitely keeping an eye on our athletes.

Q: Talk to us about your Paralympic journey that saw you compete at three different games, how did it all start?

A: I started judo pretty late, I first tried it in the summer in between leaving college and joining university. I was fortunate to live down the road from Coventry Judo Club, which was a really strong club with lots of people encouraging me. I was 18 but then took a break when I started university until I was about 21. I was doing a media degree, and I remember sitting with my friends and joking about making a documentary on me becoming a Paralympic athlete. I think we should’ve made it in hindsight but at the time none of us thought I would do it. Back in 2006, we were laughing about me taking judo up again and how we should film it, by 2008 I was competing and medalling at the Beijing Paralympics.

I loved being part of the performance side of sport, I had to sacrifice a lot like going out with friends, relationships and travelling but at the same time if I was to get a normal job and spend my weekends just going out I would be wishing I was a paralympic judo player. I had a great time.

Q: When did you start to realise that competing at the Paralympics would be possible?

A: I went to the World Championships in Sao Paulo, Brazil in 2007. I’d been to a couple of European Championships before but this seemed a really big deal. I went along and had four contests. Two people were a decent scrap which I won but I unexpectedly beat a French Paralympic silver medallist Olivier Cugnon de Sevricourt. I beat him and got into the final so being a world medallist opened up that door for me, it allowed me to get funding support and British Judo helped me take training more seriously. Before I competed in Brazil, I aimed to compete in London in five years but my result propelled me to Beijing where I got a bronze. I’d put it down to simply being able to take an opportunity. It came along, I was in the right space in my personal life and there was an opportunity to do something which I went after wholeheartedly. After Sao Paulo, I made the move to Edinburgh to train full-time.

Q: What was it like being Visually Impaired and training full-time at our National Training Centre?

A: People with disabilities are part of our lives, they exist and we encounter them. I look back on my time as a performance athlete here and think about what I got. I got lifts from people, I got support in all sorts of ways. When I first came was I up to the level of international players who were excelling? No, probably not. For a long time, I thought I was taking but there is some give there as well. Most people in society haven’t spent time with disabled people. It’s really positive that now we’ve had a whole group of performance athletes that will go out and run their clubs that have had experience of being around people with visual impairments for a long time. They start to learn that disability is second to the person. I think my time here was welcoming and the coaches and athletes supported me as best they could. A lot of that is not fancy, it’s as easy as picking me up from Haymarket as they drove past, but for ten years. They’d do their best to pick me up and I’d be there on time. It’s really simple stuff like that.

What is it like to experience the Paralympic Village?

I’ve been around a lot of visually impaired people, when you go into the village at the games you see a modern environment where everything has pretty much just been built. All of a sudden, there is access everywhere. People can get on any bus they want and there is a wheelchair ramp, it sounds obvious but everything is designed with Paralympians in mind. You realise by contrast how difficult the real world is. For example, if you’re going to get a coffee in the village there is low shelves for people in wheelchairs and all the signs are larger for those who are visually impaired. But when you get out you see the clash, no ramps anywhere and the signs are tiny. I’ve never seen it before with how disabled people are proud to be disabled. Once you are in the village everyone’s guard is let down. It’s a special place where people can laugh with each other there is a strange mood of ultra competitiveness combined with a friendly atmosphere.

And finally, what do you believe is the most important factor in ensuring the future success of the Paralympics?

The Paralympics wouldn’t be possible without the support of clubs and infrastructures like those in judo. For events like the Paralympics to thrive, sports need to be nurtured at the grassroots level. Sometimes there can be a sense of disconnect, but as long as clubs within our organisation and others remain active, the Paralympics will continue to flourish.

For more information about Visually Impaired judo in Scotland, check out our page here.